The Harpy Eagle: Seeking Hope for a Fading Symbol of Tropical Wilderness

The mighty Harpy Eagle is no match for bulldozers and rifles. But targeted and enduring conservation efforts may help save this elusive raptor and its dizzyingly biodiverse habitats.

Ecuador's coastal lowland forest and Brazil's tropical Atlantic Forest … two ecosystems at different sides of the expansive South American continent. Each hosts a distinct and diverse ark of endemic species. And well more than 90 percent of each has vanished over the last century. Separated by more than 3,000 miles, the approximate width of the lower 48 U.S. states, these disparate and disappearing wild places also represent the western and eastern extremes of the Harpy Eagle's range in South America, if only for now.

Like the Jaguar, another iconic predator sharing a similar range and fate, the mysterious Harpy Eagle presents a challenge to humanity: Will we be able to sustain wilderness areas large enough and well-protected enough to perpetuate the full complement of species found there? There's much reason for doubt, given humanity's proclivity toward road-building, forest-clearing, fire-setting, and hunting without controls, yet there is still hope. Dedicated conservation efforts, recent observations, and research are helping to piece together what it will take to save the Americas' largest eagle, and which ways of working the land might lead to a brighter future for these birds.

Harpy Eagle and chick. Photo by feathercollector/Shutterstock

Going the Way of the Jaguar

Weighing up to 20 pounds, with talons matching Grizzly Bear claws for size, the Harpy Eagle is the “Jaguar of raptors.” Wingspans of females, which are considerably larger than males, reach more than seven feet. Head, body, and tail stretch beyond yardstick length. Rarely seen sitting in the open or soaring, the Harpy Eagle stealthily tracks arboreal prey within the shady lowland and submontane forest interior. Favored targets include primates as large as howler and woolly monkeys, sloths, and prehensile-tailed porcupines. But Harpy Eagles can strike on the forest floor, too, occasionally preying upon young deer and peccaries. The colossal slate-and-black raptor will also grab macaws, turkey-sized curassows, iguanas, snakes, and other creatures.

As with the Americas' largest cat, the Harpy Eagle's range looks ample when colored in on a map. Historically, this mighty raptor was found from Mexico to northern Argentina, a broad range often cited as a reason why it will always persist. But recent models incorporating satellite imagery sharpen the view, showing how generously shaded maps belie reality — to Harpy Eagles, much of this range is no longer habitable.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) currently lists both the Harpy Eagle and Jaguar as Near Threatened, due to widespread habitat loss and hunting. Many experts say the situation for both species is more severe than previously recognized, and that their status should be changed at least to Vulnerable. The eagle may already be extirpated from Mexico, although photos and other documentation indicate its recent presence along the country's border with Guatemala. The species is still reported in Honduras, Nicaragua, and Belize, but only in a few remaining wilderness zones, where northern Central America's last large contiguous forests remain — in places like Nicaragua's Bosawas Biosphere Reserve and the adjacent Honduran Patuca National Park, which in recent years have faced large-scale incursions by settlers, along with reported shooting and capture of Harpy Eagles. The species barely hangs on in Costa Rica, with only a few sporadic reports in the country.

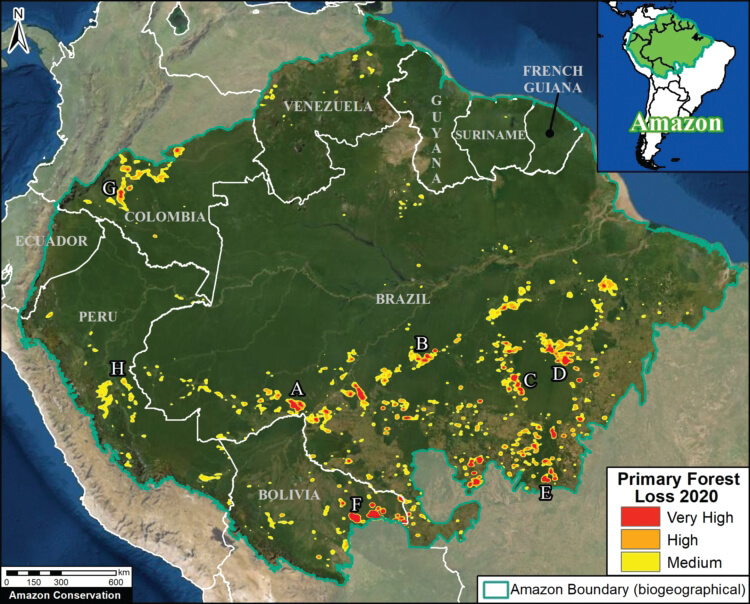

Chipping away: Primary forest loss in 2020 in Amazonia. SOURCE: MAAP/Amazon Conservation

Even the greatest remaining forested wilderness, Amazonia, is contracting dramatically, its edges drawing inward like a great drying puddle, yielding to the advances of ranching, roadbuilding, soy and other farming, settlements, and fires that march across the drying landscape. Ragged forest fragments and edges are quickly degraded by further cutting. Guns are prevalent in the region and newly cut roads immediately facilitate subsistence hunting. The hunting winnows down both the Jaguar's and the Harpy Eagle's prey base, but guns are also trained on the predators as well. And Harpy Eagles provide huge, sometimes unwary targets.

Pushing aside the notion that the eagles are just fine in the core of their South American range, a study published in the online journal PLOS ONE in 2019 estimates that 93 percent of the Harpy Eagle's current distribution is in Amazonia, where habitat is being lost at alarming rates. The authors write: “Our distribution range for this species represents a 41-percent reduction of what is currently proposed by IUCN.” From the south, a broad front of livestock ranges and soybean fields continues to chew into the region's forest wilderness. This advance is already estimated to have claimed almost a quarter of Amazonia's old-growth terra firme, or non-flooded, forests.

A University of Plymouth study published this year in Ecology and Evolution estimated that the bird's range is 11 percent smaller than previously estimated. This study also analyzed climate-related data, and the researchers projected that in coming years, northern South America and Panama will provide the most climatically stable refugia for the eagles and their habitat. The study's lead author Luke Sutton says, “Our study shows that predicted future climate stability will be in core areas with extensive lowland tropical forest habitat. That means habitat loss as a result of deforestation is the greatest threat [the birds] face, and conservation plans need to take all of that into account.”

Compounding the shrinkage in range is the fact that the Harpy Eagle is one of the slowest breeders in the bird world. A pair raises, on average, one chick every two-and-a-half to three years. This slow reproduction means that every eagle lost impacts a population. Unfortunately, the leading known cause of adult mortality is gunshots.

Even in expansive prime habitat, these eagles are naturally scarce. In Amazonia, for example, an estimated three to six nests occur per 100 square kilometers, which converts to 38.6 square miles or 24,700 acres — more than half the size of Washington, D.C.

Harpy Eagle. Photo by Tanislav Harvančík AR7Q3796/Shutterstock.

Conservation and Commerce?: A Raptor's Rocky Road

A Biological Conservation study published in 2020 illustrates why Harpy Eagles frequently vanish when the chainsaws start screaming. The authors noted that Harpy Eagles usually place their bulky stick nests — on average, five feet by three feet — in forks of massive trees with crowns poking above the surrounding forest canopy, and that 93 percent of the tree species they favor are also prized by the timber industry. The authors write that given their finding that foresters target the same species and the largest individual trees, they question “whether large tracts of selectively logged Amazonian primary forests still provide suitable nesting habitat for this mega-raptor.” They conclude that “suitable Harpy Eagle nesting trees have been rapidly lost over the species' last stronghold….”

Throughout Amazonia, hunting eagles and other wildlife is now far easier due to the widespread availability of firearms. Eagle feathers are also used in illegally sold handicrafts that fetch high prices. Meanwhile, resettlement initiatives and illegal forest cutting continue to push into wilderness, with guns following. How, then, might Harpy Eagle conservation be combined with human activities? Securing declared protective reserves, and buffering core areas with sustainable activities and strict eagle-hunting bans could yield results. On occasion, Harpy Eagles are found in habitats that have undergone some forest clearing. But this is far more the exception than the norm. And these “in-plain-view” birds might be vagrants or not able to breed due to lack of nesting trees.

Pockets of Hope

Almost extirpated from tropical Atlantic Forest, the Harpy Eagle is making a last stand in a few places. One of the largest is Serra Bonita, an isolated forested range of hills in Bahia State in eastern Brazil. There, conservationists Vitor Osmar Becker and Clemira Ordoñez Souza established and have been working with partners, including ABC, to expand and maintain the Serra Bonita Complex of Private Natural Heritage Reserves, which currently spans 7,413 acres. At latest count, Serra Bonita Reserve is home to more than 1,000 vascular plant species, about 5,000 recorded butterfly and moth species, 70 frog species, and 400 bird species, including 70 Atlantic Forest endemics, two new to science. In all, 20 new animal species have been documented on the property, as well as 15 new plants.

Some of the protected lands are owned and managed by a nonprofit group the couple founded in 2001, called Instituto Uiraçu — using the Harpy Eagle's name in the indigenous Tupi language, meaning “big bird.” Becker and Souza knew the Uiraçu once occurred in the area, but that it was teetering on the brink. Then, in 2010, a team of observers photographed an immature bird in the reserve, and found feathers from the species on the forest floor. In 2018, observers from the organization Projeto Harpia (of which Instituto Uiraçu is a partner) located an active nest in the reserve. “The species still occurs in Serra Bonita,” says Souza. “Although the nest fell from its tree at the beginning of 2020, vocalizations of the species have been heard by the park rangers at the end of the year.”

Harpy Eagle and chick. Photo by João Marcos Rosa/NITRO.

Souza has thoughts on why Harpy Eagles inhabit the property. “The size of the reserve, structure of the forest, and availability of prey are adequate for [the species]. Also, other nearby reserves have records…. It is likely that the Harpy Eagle was present in Serra Bonita even before the reserve was actually created,” she says. “It is also possible that it may have dispersed from other nearby areas.” Such is the way of the Harpy Eagle, a bird rarely seen and hard to consistently monitor.

But an important point is that effective conservation in southern Bahia seems to be allowing Harpy Eagles to persist there. A similar situation is occurring in southern Belize, which is now losing its once-extensive forests at a rapid rate. There, in 2018, the Harpy Eagle was seen for the first time since the founding of a 1,153-acre reserve and research center by the Belize Foundation for Research and Environmental Education. The property adjoins Bladen Nature Reserve and the Maya Mountains; together these areas comprise one of the largest remaining forest blocks in the region.

In the Chocó region of northwestern Ecuador, a similar scenario plays out. Extensive lowland forests rich in endemic species only persist in a few large patches. Here, too, recent Harpy Eagle sightings and the first-known nesting in ten years raise hope that the species can hang on, along with other imperiled species such as the Critically Endangered Great Green Macaw and the Endangered Brown-headed Spider Monkey.

ABC is working with Fundación de Conservación Jocotoco (Jocotoco) and other partners to expand private reserves and join them with a large national reserve nearby, creating a wildlife corridor that will ensure protection of the full range of the region's biodiversity. Among these properties is Jocotoco's Río Canandé Reserve, one of six reserves in ABC's and partner's network where this species has been recorded. (Others include another reserve in Ecuador, Serra Bonita and another reserve in Brazil, and locations in Peru and Colombia.)

Harpy Eagles prey on a wide variety of rainforest animals. From left: Brown-throated Sloth by Damsea/Shutterstock; Brazilian Porcupine by Davydele/Shutterstock; Red Howler Monkeys by Salparadis/Shutterstock

Nearby, ABC is also embarking on an impact investing project with partners Verdecanande and Jocotoco. The goal is to selectively harvest wood on commercial forestry land, but at a low volume, without having to take just the biggest and most valuable trees — and without adding roads to access the timber. By creating sustainable flooring and furniture products from a large mix of trees that can be moved out of the forest by cable, the forest can provide valuable timber income and associated jobs, while maintaining structural diversity including super-canopy trees used by species like the Harpy Eagle and Great Green Macaw. This type of approach could provide protected acreage and areas where species such as Harpy Eagles can hunt for their food, if they were to return. To start, a study area of approximately 500 acres is being evaluated using sound meters, to record the species diversity occurring in the area before any activities occur, so the impact of tree removal can be evaluated.

Will the Harpy Eagle survive into the next century? Knowing how much and what quality habitat the eagle requires will be essential as we move forward. If current trends continue, this bird and also the Jaguar may become memories — mystical creatures of lore. But if we protect large areas of forest, and balance conservation with sustainable activities of a growing population, maybe there will be a promising future for the “big bird” and the myriad of other species sharing its amazing habitats.

| Howard Youth is ABC's Senior Writer/Editor, and is the author of Field Guide to the Natural World of Washington, D.C. |