Ring-billed Gull map by ABC

The widespread Ring-billed Gull is a familiar sight across most of North America. In adult plumage, this mid-sized gull is pure white with a pale gray back and wings (called the “mantle”), and black wingtips dotted with white. Its eyes, legs, and bill are yellow, the latter with the namesake black ring near the tip. A thin ring of red encircles each eye. During the winter, this gull shows dark brown streaking on its head and neck, and the red eye ring turns black.

The Ring-billed Gull belongs to the family Laridae, a group of predominantly coastal bird species that includes other gulls such as the Laughing Gull, terns including the Royal Tern, and the Black Skimmer. Like other members of its family, this gull is highly gregarious, with nesting colonies and feeding flocks sometimes reaching thousands of individuals.

Although many people call these birds and their relatives "seagulls,” the Ring-billed Gull often defies that stereotype.

Ocean Optional

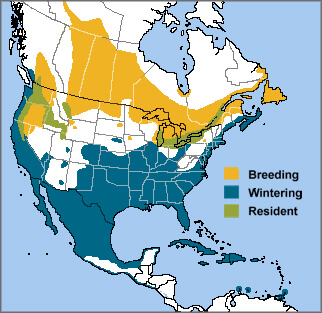

Although some Ring-billed Gulls live near coastlines, many spend the majority of their lives along inland waterways. This gull takes to fresh water as easily as salt, and individuals can go their entire lives without dipping a foot in the sea. The “Ringbill” breeds on islands in rivers, lakes, and marshes, from the prairies of Canada south to central California, and in the Great Lakes region, the Canadian Maritimes, and northern New England. Winter finds the gulls migrating to places with open water, often to the East and West Coasts, as well as to lakes and rivers of the south-central United States, into Mexico and the Caribbean.

Magnetic Migrant

The Ring-billed Gull is a mid- to long-distance migrant, moving south by day in large flocks, navigating by following physical landmarks, including major river valleys and coastlines. As is likely the case in many migratory bird species, this bird is also able to use Earth's magnetic field to orient itself — basically having a built-in compass that guides it in the right direction as it migrates. Researchers have found that even two-day-old Ring-billed Gull chicks possess this ability.

Some Ring-billed Gull populations are resident (nonmigratory), particularly those found near and around the Great Lakes.

The Ring-billed Gull is a fairly noisy species, with a number of loud calls. Listen here:

(Audio: Thomas Ryder Payne, XC636397. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/636397. Paul Marvin, XC461003. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/461003.)

Fast Food Gull

Like the American Crow and Common Raven, the Ring-billed Gull is an opportunistic feeder and scavenger. Many call this bird the "fast food" or "french fry" gull, as it's often spotted hanging around restaurant dumpsters in search of a meal. It also frequents landfills, parking lots, lawns, and agricultural fields, especially when tractors and other farm vehicles stir up worms and other invertebrates. In addition, this intrepid gull readily steals food from other birds and even unwary people.

The Ring-billed Gull's varied diet doesn't stop at leftovers: Foraging on foot, in flight, or while sitting on the water's surface, it also feeds on fish, insects, crabs, bird nestlings and eggs, grain, and small rodents.

Model Parents

The Ring-billed Gull nests in large colonies, sometimes alongside other gull or tern species. Colonies are typically located on low-lying islands in freshwater lakes or marshes, places that provide protection from terrestrial predators.

Ring-billed Gulls at nest with chicks. Photo by Kathryn Carlson, Shutterstock

Ring-billed Gulls are mostly monogamous, with pairs forming after the birds arrive at their breeding grounds — usually in the same colony where they hatched. Gull courtship is an interesting mix of physical posturing and vocalizations. The male offers the female food as well. Once mated, the breeding pair cooperates in defending territory, building a nest, incubating eggs, and feeding and raising their young.

The Ring-billed Gull's nest is a large, bulky assemblage of twigs, leaves, mosses, lichens, and other vegetation, built in a scrape on the ground. There, the female lays her clutch of two to four light-colored, brown-splotched eggs. Within a few days of hatching, the chicks begin walking around the nest area. After about five weeks, they can fly.

As juveniles, Ring-billed Gulls have streaky brown plumage. They go through several more plumages before attaining full adult coloration in their third year. This multi-year plumage transformation, seen in other gulls as well, allows young birds time to learn the foraging skills they will need to successfully provision their own mate and young, which usually happens after reaching adult plumage.

A Conservation Numbers Game

Along with other colonial-nesting bird species such as the Brown Pelican, Roseate Spoonbill, and Great Egret, the Ring-billed Gull was almost driven to extinction by egg collectors and plume hunters in the late 19th century. The establishment of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918 allowed the gull's numbers to recover, and North America's ever-growing suburbs and landfills became an important source of food.

Ring-billed Gull numbers have bounced back to such an extent that their large colonies sometimes pose a threat to smaller species, including threatened birds such as the Piping Plover. Large gull colonies in urban and suburban areas can also impact airline flight safety, human health, and agricultural productivity. On occasion, Ring-billed Gulls are subjected to control efforts, done with proper permitting through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

ABC monitors bird-control efforts, and often joins partners in speaking out against unwarranted persecution of gulls, cormorants, and other bird species that might be labeled as “nuisances.”

Donate to support ABC's conservation mission!