Invasive Ants in Hawai'i: Small Species, Big Problems

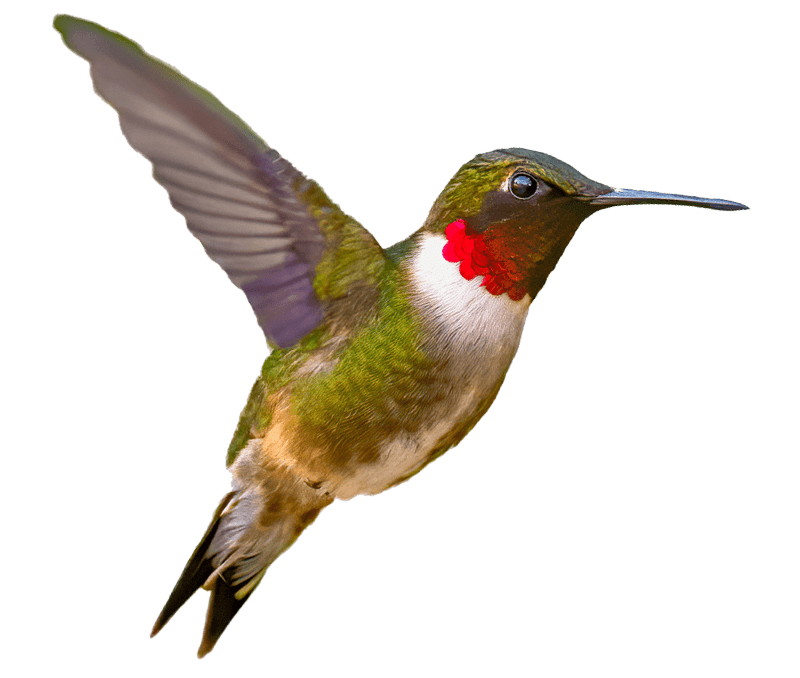

One of the biggest problems facing Hawai'i's endemic birds is invasive species: plants and animals from other areas of the globe whose populations dramatically increase in their new island home. Miconia (a large tree), strawberry guava, and many other plants outcompete and replace Hawai'i's native plants. Grazing mammals degrade and destroy the forests. Cats and mongooses prey upon the birds. Even smaller, less noticeable species such as invasive ants can have great impacts on native ecosystems, especially on seabirds.

Yellow crazy ants (Anoplolepis gracilipes) arrived in Hawai'i in 1952 from the Old World tropics and have had large-scale impacts on the ecosystem. Photo by Alex Wild

No People, No Invasive Ants

The Hawaiian chain is one of the most isolated groups of islands in the world, and before people arrived there were no ants. Over the last two centuries roughly 57 ant species have become established on the various islands, and at least four ant species have had particularly profound effects on native insects, spiders, and the larger ecological communities.

The most troublesome species include the big-headed ant, tropical fire ant, Argentine ant, and yellow crazy ant. These ants are so successful because they eat a wide variety of plants and animals. They form multi-queen nests and have multiple nests that form a single “supercolony,” resulting in very large numbers. And they display very low aggression within their species but high aggression to arthropods and other animals.

The Predator Problem

The problem is exacerbated by the lack of predators or parasites of ants that would be present in their original ranges to keep them in check. Colonies can reach incredibly high densities on the islands. As a result, invasions by these ant species alter food webs, reduce native insect food available for birds, and decrease the abundance of native plants and their pollinators.

They can eat plant seeds and reduce the number of native bees and moths that pollinate the native plants, thereby lowering the number of seeds produced. Ants will also exclude pollinators from nectar sources such as 'ohi'a blossoms, which also lowers the number of seeds produced.

Ants and Seabirds

Seabirds in the Hawaiian Islands did not evolve with ants present, so they have no defenses against the invaders. Big-headed ants will chew, and tropical fire ants will sting, birds' exposed fleshy parts. Yellow crazy ants spray formic acid and irritate exposed areas such as the eyes, bill, and feet. The injuries to nesting seabirds can be extreme, including loss of webbing on their feet, malformed bills, difficulty breathing (due to injury to the nasal cavity), and inflamed eyes or overgrowth of skin around the eye that can lead to blindness.

Adult birds will sometimes fly away to avoid the ants or abandon their nest sites completely, but if somehow they do persevere during incubation and hatch their eggs, the chicks are unable to escape and suffer countless attacks by ants. These injuries translate into reduced fledgling success and in some cases cause abandonment and even permanent loss of the breeding colony.

This Wedge-tailed Shearwater chick has suffered severe ant damage to its eye and bill due to ant attacks. Photo by Sheldon Plentovich/USFWS

Sheldon Plentovich, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's (USFWS) Coastal Program Coordinator, has spent many years studying the impacts of ants on seabirds. “The effects of ants can be catastrophic to the breeding seabirds and are going to become more common as these highly invasive species spread,” she said.

USFWS Taking Action

Plentovich is involved in several projects to eradicate ants from selected Hawaiian Islands. An important one is on Johnston Atoll, located in the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument. This is the only rat-free area for about 750,000 square miles of the Pacific Ocean. As a result, the islands support huge numbers of breeding Red-tailed Tropicbirds, Sooty Terns, Red-footed Boobies, Wedge-tailed Shearwaters, Great Frigatebirds, and many other seabird species.

This Red-tailed Tropicbird is covered with yellow crazy ants on Johnston Atoll. Photo by Stefan Kropidlowski/USFWS

Unfortunately, Johnston was also home to a huge population of yellow crazy ants. Nests with 800 to 1,000 queens—more than three times the density in their native habitat—were producing huge numbers of ants, with widespread negative impacts on the seabirds.

USFWS established the “Crazy Ant Strike Team” on Johnston Atoll in 2010 to lead an aggressive effort to eradicate the yellow crazy ants. They have had great success, reducing ant abundance to less than five percent of the original population. (See update at the end of this story.)

Achieving complete eradication has been complicated by Johnston's remote location, difficult terrain, and ant baits that have not been as effective here as at other sites. The committed team continues to test, modify, and deploy new baits and approaches that they hope will eventually remove the last yellow crazy ant queen.

Battling Yellow Crazy Ants Around O‘ahu

Ant problems also exist on most of the approximately 15 small islets off the coast of O'ahu. While the smaller sizes of the islets means that eradication might be more feasible than on the larger islands, careful study needs to precede any management actions. When big-headed ants were removed from Mokuauia, for example, the population of the even more problematic yellow crazy ants exploded.

Big-headed ants (Pheidole megacephala), originally from Africa, likely eliminated whole suites of insects and other arthropods when they arrived on the Hawai'ian Islands at the turn of the 19th century. Photo by Alex Wild

“We have to be careful when implementing ant control measures because the removal of one species leaves resources available for other invaders, including more harmful ant species,” said Plentovich of her experiences on the offshore islands.

Yellow crazy ants are also a problem on O'ahu itself. These ants are reducing nesting success and causing significant abnormalities in Wedge-tailed Shearwater chicks at Kāne'ohe Bay. USFWS will conduct focused control of yellow crazy ants at Kāne'ohe and Mokuauia during the upcoming shearwater breeding season to reduce impacts to the chicks.

Plentovich hopes that the ants' impacts can be curtailed. “I am optimistic we can control yellow crazy ants in these colonies and allow these seabirds to return to their pre-invasion breeding levels,” she said.

Unwelcome Arrivals

Unfortunately, new species continue to arrive in the state. The little fire ant arrived on the Big Island in 1999 and is damaging crops, promoting pest insects, and aggressively stinging people and pets. This ant species subsequently spread to Kaua'i, where a large infestation is being actively controlled by the state of Hawai'i.

USFWS technician applying bait to yellow crazy ant colonies on Johnston Atoll. Photo by USFWS

The Kaua'i infestation is already a problem for all the birds breeding in this area. Continued ant control and containment is particularly important because other critical locations are nearby, including Kīlauea Point National Wildlife Refuge, a key seabird site and location of a predator-proof fence built to benefit nesting Hawaiian Petrels and Newell's Shearwaters. (This fence was constructed by Pacific Rim Conservation, ABC, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service with National Fish and Wildlife Foundation support.)

Several little fire ant infestations have also been found on Maui and O'ahu. Although the ants are no longer detected at some smaller sites, populations in larger areas have only been contained so far. New outbreaks continue to occur, indicating that the current quarantine and inspection measures are insufficient.

A Tipping Point?

The constant influx of invasive species—ants as well as all the other groups of organisms—is one of the most serious problems facing Hawai'i's native species. Governor David Ige recognized this when he proclaimed Invasive Species Awareness Week. The state's legislature acknowledged this, noting that invasive species are “the single greatest threat to Hawai'i's economy and natural environment and to the health and lifestyle of Hawai'i's people.”

Even with this support, the Hawai'i Department of Agriculture is underfunded and does not have the resources necessary to inspect all the goods coming into the islands. Until more rigorous inspections of cargo, including shipments between the islands, can be undertaken, new invasive species may continue to take hold in Hawai'i, with devastating impacts on birds and native ecosystems in what is already our most endangered state.

However, with the recent arrival of such high-profile species as little fire ant causing public concern, and the increased awareness in the political sphere, we are hopeful that the state has reached a tipping point. In the near future, perhaps we will see dedication of resources necessary to adequately address the threat from invasive species to Hawai'i's unique and irreplaceable plants and animals.

Author's Update: This story appeared in a 2015 edition of our Bird Conservation magazine. Conservation successes can be difficult out here, but with support and resources the dedicated biologists working in Hawai'i can accomplish near miracles. An an example, a recent article from Scientific American (Conservation Predictions for 2017) speculates that invasive yellow crazy ants might be fully eradicated from Hawai'i's Johnston Atoll by the end of this year.

Curious, I reached out to Sheldon Plentovich, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Coastal Program Coordinator, for an update on their efforts to eradicate the ants from the 70 acres that are infested. She shared the following reply with me:

“The Yellow Crazy Ant Strike Team has achieved significant progress toward eradication of these ants from Johnston Atoll. Yellow crazy ant numbers are down over 95 percent and this has translated into substantial benefits to ground-nesting seabirds such at Red-tailed Tropicbirds. Although there was a 13-week period where no yellow crazy ants were detected, the ants still occur at low densities and we won't be able to say they are eradicated until they are not detected for a long period of time (i.e., 3–5 years)."

After their years of hard work, this is very encouraging progress.

– Chris Farmer, ABC Hawai‘i Program Director

For more about yellow crazy ants, check out the Islands issue of BBC's Planet Earth II documentary.

Chris Farmer is ABC's Hawai‘i Program Director and has been working with endangered birds and conservation for over 25 years. He has been studying the ecology of Hawaiian birds for the last 13 years, including leading translocations of Palila and Millerbirds. His research has also addressed the impacts of exotic predators and ungulates on native ecosystems, and forest restoration and recovery.

Chris Farmer is ABC's Hawai‘i Program Director and has been working with endangered birds and conservation for over 25 years. He has been studying the ecology of Hawaiian birds for the last 13 years, including leading translocations of Palila and Millerbirds. His research has also addressed the impacts of exotic predators and ungulates on native ecosystems, and forest restoration and recovery.