In the Bronx, Testing New Ways to Prevent Birds from Hitting Windows

Early on a cloudy fall morning, I edge carefully down a steep, forested hillside along the Bronx River, following avian testing technician Emilio Tobon as he checks the mist nets he opened before sunrise.

The Bronx doesn't automatically come to mind when you think of forests, but this area, on the grounds of the Bronx Zoo, are thick with good-sized oak and hickory trees. The rock-studded hillside bottoms out along the river into flooded, flat areas choked with willow trees and underbrush.

Emilio Tobon, an avian testing technician with New York City Audubon, opens mist nets along the Bronx River. Photo by Gemma Radko

I'm visiting this patch of urban wilderness to learn more about important research ABC and New York City Audubon are conducting. With birds captured in the mist nets, the two organizations are researching and testing ways to prevent birds from hitting windows.

As we follow muddy trails alongside the river, I hear Belted Kingfisher, Wood Thrush, and Gray Catbird calling. The mist nets set up alongside the river yield a good catch of birds: an Ovenbird, a Swainson's Thrush, and a Black-and-white Warbler. We quickly extract the birds from the nets, place them in soft cloth bags, and carry them back up the steep hillsides to the testing facility. Awaiting me there is Christine Sheppard, ABC's Bird Collisions Campaign Manager and my guide for the day.

Tobon's mist nets along the river yield a good catch of birds for testing, including a Black-and-white Warbler. Photo by Greg Homel

The Threat of Glass

People learn about glass at an early age. Even though clear glass is invisible, there are architectural cues that tell us where to expect glass and how to steer around it. Birds don't learn this lesson.

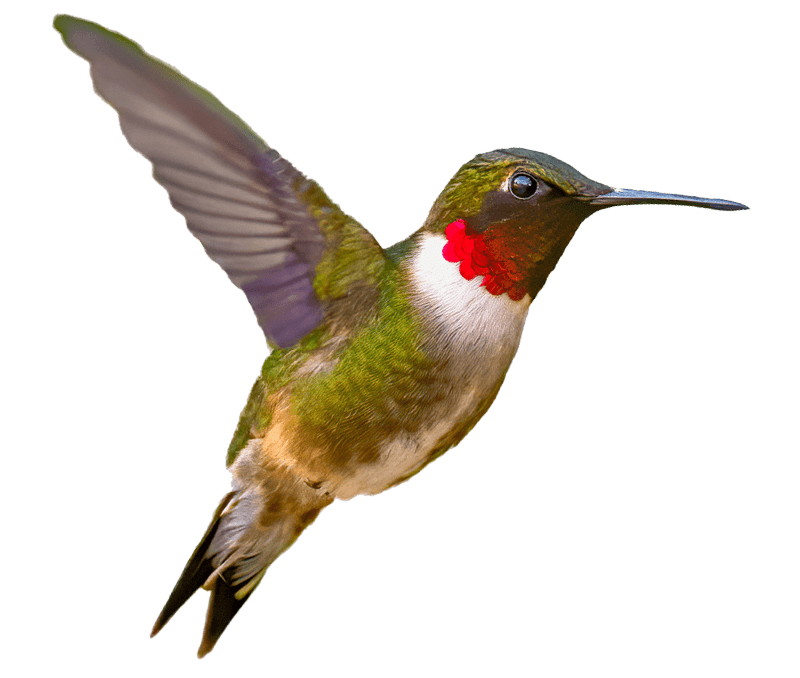

Up to 1 billion birds die each year in the United States when they hit windows, making this threat one of the most costly to bird populations. Migratory and backyard birds are among the most common victims, including species such as White-throated Sparrow, Painted Bunting, and Ruby-throated Hummingbird.

Up to 1 billion birds die in the United States each year after colliding with glass. Photo by Barbara Carlse

In 2004, Austrian ornithologist Martin Rössler developed a research method to adapt glass so that birds avoid it. Rössler's “tunnel testing” provides a safe way to give birds in flight a perceived choice between exiting a dark space by way of a plain piece of glass, or one with a pattern.

The patterns are combinations of elements of different sizes, shapes, color, spacing, and contrast, with different orientations and levels of opaqueness. If most birds fly towards the plain glass, the assumption is that the pattern creates a visible barrier that the birds will avoid.

Migratory and backyard birds, including White-throated Sparrow, are the most frequent victims of colliding with glass. Photo by Jacob Spendelow

“Birds see differently than we do,” Dr. Sheppard tells me. “Their contrast sensitivity is not as good as ours, so there are patterns they may not see. The contrast, spacing, and size of a pattern all matter.”

Tunnel Vision

In 2008, Dr. Sheppard, then curator of birds at the Bronx Zoo, received a grant from the Association of Zoos and Aquariums to partner with New York City Audubon and the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in building a test tunnel at the museum's Powdermill Nature Reserve, in Pennsylvania. (The program moved to ABC in 2009.)

Powdermill's research has already confirmed several important findings. For instance, horizontal lines or other patterning on glass must be two or fewer inches apart to deter the majority of birds, and vertical lines must be four or fewer inches apart. These lines can be wavy, on an angle, or even broken into segments; they can be integral to glass or applied to the surface.

These dimensions work for small species, such as warblers, and for larger birds as well, because birds are able to assess the size of the gaps relative to their body size and adjust their flight behavior accordingly.

Down the Hatch

Back in the Bronx, I learn more about how this newer facility is helping to save birds. The tunnel, a 24-foot plywood box on legs constructed within a metal shipping container, was built by ABC and New York City Audubon in 2013 with funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. It doesn't look like much from the outside, but this tunnel is generating research that could save the lives of millions of birds.

The tunnel-like testing facility in the Bronx where researchers are testing patterns on glass. Photo by Gemma Radko

Tobon bands and records the species, age, and sex of each captured bird. Then we place each bird in a small hatch at the entrance of the tunnel, where it faces a long, dark passageway. At the far end are two lighted pieces of glass: one unmodified (the control) and the other with a pattern to be tested.

As each bird darts down the tunnel, we note which way it tries to exit—control or pattern—using a video camera to record the attempt. A strategically placed mist net prevents the birds from slamming into the glass. After recording each response, one of us opens a door at the far end of the tunnel, and the bird flies out.

Future Goals

It's still early days at the Bronx tunnel, which aims to build on the research already accomplished at Powdermill. One significant advance: Since it's built in a shipping container, this tunnel can control the amount of light available during testing—a condition not always achievable at the free-standing Powdermill site.

The artificial light source in the Bronx tunnel can simulate two different levels of daylight: with or without ultraviolet. This will further standardize testing, helping to score different materials under varied lighting conditions. The same window can look different at different times of day, in different weather, and even on different sides of the same building.

If most birds fly towards the plain glass (right), the assumption is that the pattern (left) creates a visible barrier that the birds will avoid. Photo by Gemma Radko

ABC has already rated 18 products tested in the Powdermill tunnel as being effective in significantly reducing bird collisions with glass. (Visit our Bird Smart Glass program to learn more.)

Six of these products are consumer materials meant for homeowners, 14 are commercial products for architects and building managers, and two of the products are appropriate for both settings. The list of Bird-Smart glass products will continue to grow as new products are tested and found effective.

After several hours of helping at the tunnel, I realize that there is no easy way to fix the problem of bird collisions. ABC and researchers around the world need to keep pursuing all possible avenues of research—including this tunnel protocol—to develop a sophisticated and permanent solution.

Gemma Radko is ABC's Communications and Media Manager. She graduated from Allegheny College with degrees in Art and Biology and has over 20 years of graphic design, writing, and editing experience. Gemma is an avid birder and is a member of both the Montgomery and Frederick chapters of the Maryland Ornithological Society, often leading field trips for members. A licensed bird bander, she has in the past run a MAPS (Monitoring Avian Productivity and Survivorship) station.