The Black-footed Albatross is the only one of its kind commonly seen off the North American coastline. It's rather small as albatrosses go, but still impressive, with a six-foot wingspan. Its species name, nigripes, derives from two Latin words, niger meaning "black," and pes meaning "foot."

The Black-footed Albatross is the only one of its kind commonly seen off the North American coastline. It's rather small as albatrosses go, but still impressive, with a six-foot wingspan. Its species name, nigripes, derives from two Latin words, niger meaning "black," and pes meaning "foot."

Although drift nets and longline fisheries remain constant threats, the Black-footed Albatross faces a gauntlet of newer challenges: invasive predators and introduced plants on nesting islands, ingestion of plastics, and climate change.

More than 95 percent of the world's population of Black-footed Albatross nests in the remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, with the largest colonies on Midway Atoll and Laysan Island. (Laysan is also home to the recently introduced Millerbird.) Although these islands are protected, they are vulnerable to the effects of sea-level rise and increased storm intensity.

Life over the Ocean

Black-footed Albatrosses are beautifully adapted for a life at sea and can remain airborne for hours, landing only on the water to rest or feed. Their specialized tubular noses (found among many seabirds, including Hawaiian Petrel and Newell's Shearwater) filter salt, allowing the birds to drink seawater and giving them an excellent sense of smell.

This keen sense helps the albatross locate its prey over vast expanses of ocean. Favored foods include flying fish (both eggs and adults), squid, crustaceans, and offal thrown from ships.

They forage by seizing prey at the surface, up-ending to reach underwater, or diving short distances with wings partly spread.

Sign up for ABC's eNews to learn how you can help protect birds

Faithful Partners, Devoted Parents

Like other albatross species, including Laysan and Waved, this bird is slow to mature, not breeding for until five years or older. It also has a low reproductive rate and mates for life.

Males are the first to arrive on the breeding grounds, where they re-claim the nest site that the bird and its partner may have used for many years. The strong pair bond shared by these birds is established and maintained through elaborate displays, including bowing, mutual preening, and head-bobbing.

The Black-footed Albatrosses' nest, rebuilt each year, is a simple scrape in the sand, usually at or above the high-tide line in an open or sparsely vegetated area. Both birds build the nest and take turns incubating their single egg. If this egg is lost—whether to a predator or some other threat—the birds will not attempt to breed again until the following year.

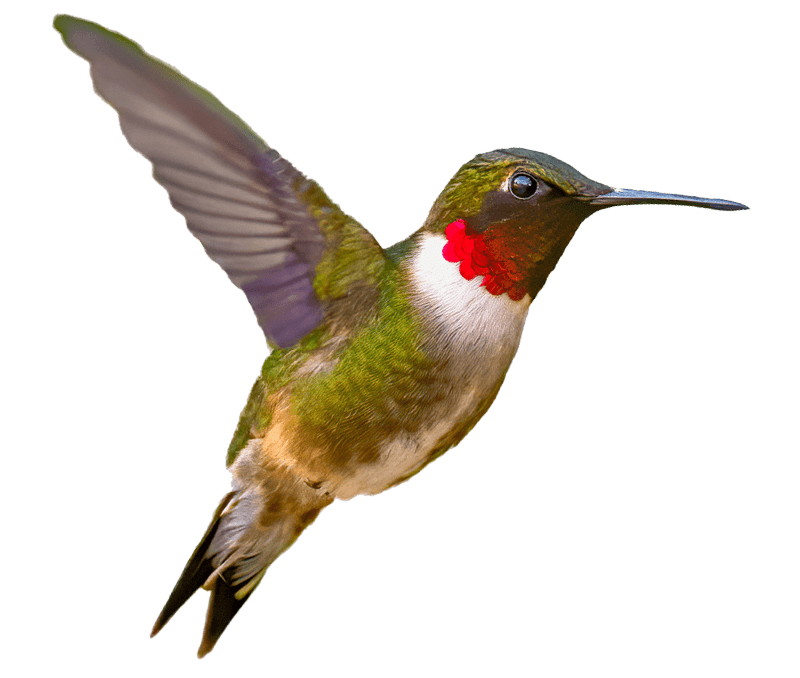

Black-footed Albatross in flight, showing its impressive six-foot wingspan. Photo by Greg Lavaty

For about 18 to 20 days after hatching, one parent broods and guards the nestling while other forages for food, switching off every day or two. The chick is fed by regurgitation by both parents until it fledges, at four to five months old.

Advocating for Black-footed Albatross

The Black-footed Albatross is included on the Watch List in the State of North America's Birds 2016 report, which highlights species most in need of immediate conservation action.

ABC continues to advocate for Black-footed Albatross and other seabirds impacted by commercial fisheries. We also support legislation to ratify the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels (ACAP) by the United States. And we recently launched an interactive web-based tool to help fisheries avoid accidentally catching seabirds: fisheryandseabird.info.

ABC has also collaborated with the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and other partners to secure predator-free breeding habitat for seabirds on islands in Hawaii.

Donate to support ABC's conservation mission!