The regal-looking Canvasback is the largest North American diving duck. Its name was inspired by the male's white back and sides, which reminded English settlers of canvas fabric. The drake (male) is an arresting sight, with red-brown head and gleaming red eyes. As in the Wood Duck, the hen (female) has less conspicuous plumage, but all Canvasbacks share the same long, sloping profile and dark bill.

The regal-looking Canvasback is the largest North American diving duck. Its name was inspired by the male's white back and sides, which reminded English settlers of canvas fabric. The drake (male) is an arresting sight, with red-brown head and gleaming red eyes. As in the Wood Duck, the hen (female) has less conspicuous plumage, but all Canvasbacks share the same long, sloping profile and dark bill.

This duck's species name valisineria is a clue to its favored food, and one of the reasons the Canvasback was sought-after by human hunters.

Named for Wild Celery

The Canvasback's species name comes from aquatic Wild Celery, Vallisneria americana. Canvasback and other diving ducks feast on the roots and seeds of this native plant during the winter, which gives their flesh a delicate, celery-like flavor. Many duck hunters consider "King Can" to be one of the tastiest gamebirds, and commercial market hunting in the 19th century nearly sent this big duck the way of the Passenger Pigeon.

Fortunately, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 outlawed market hunting, an important step toward the Canvasback's eventual recovery. The creation of the National Wildlife Refuge System conserved wetland habitat for waterfowl; many of these refuges were purchased with funds generated by the Duck Stamp, another important conservation program.

Prairie Pothole Duck

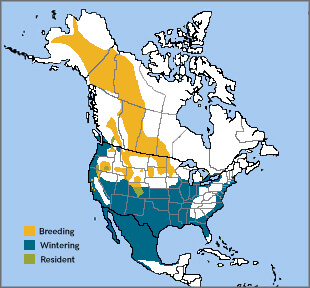

Canvasbacks breed mostly in the Prairie Pothole Region of North America, a rich complex of wetlands and grasslands that stretches over five U.S. states and three Canadian provinces. Millions of waterfowl breed in this region, earning it the nickname of "America's duck factory." Many songbird species, including Sprague's Pipit and Baird's Sparrow, also breed in the area's grasslands.

Each fall, Canvasbacks migrate south along the Mississippi Flyway to wintering grounds in the Mid-Atlantic and the Lower Mississippi Valley. Other Canvasbacks migrate south along the Pacific Flyway to winter along the California coast. From November to March, they are fairly common along the Texas coast as well, and occur patchily at inland lakes across the West, reaching, in small numbers, as far south as central Mexico. There have been some sightings in northern Central America and the Caribbean.

Brackish estuaries, bays, and marshes rich in aquatic vegetation and invertebrates are favored wintering habitat. Historically, the Chesapeake Bay harbored the majority of wintering Canvasbacks, but the continued loss of submerged aquatic vegetation in the Bay led to declining numbers of waterfowl there.

Not-So-Neighborly Nesting

The normally gregarious Canvasback becomes monogamous and secretive during its breeding season. Pairs establish and maintain their bond through mutual displaying, although the female makes the final choice of mate. Hens prefer to build their nests over deeper water amid the protective cover of emergent marsh vegetation such as cattails. The nest itself is a bulky structure of reeds and grasses anchored to the stems of marsh plants and lined with down.

Canvasback clutches range in size from five to 11 eggs. Hens sometimes lay eggs in other Canvasback nests, and Redhead ducks, well-known brood parasites, often lay their eggs in Canvasback nests. This phenomenon is dependent upon a variety of factors, including habitat and nest site quality and availability, and the parasitizing female's fitness. Ducks do not defend their nesting areas during egg-laying, which makes it easy for another female to sneak in and lay eggs. And since ducklings are precocial — they hatch covered in down and able to move about and feed themselves — the burden on the host hen is not too high.

Canvasback flock in the winter on the Chesapeake Bay by Lone Wolf Photography, Shutterstock

Diving for Dinner

Canvasbacks are diving ducks, well-adapted for foraging underwater, propelled by strong webbed feet. They often dive to depths of seven feet while foraging but can reach as deep as 30 feet. They also may dabble on or just below the water's surface. Canvasbacks feed both day and night.

During migration and winter, much of their diet consists of the rhizomes (roots) of aquatic plants, particularly Wild Celery and Sago Pondweed. Strong muscles allow these ducks to open their bills even under the mud – a helpful adaptation for excavating plant roots.

During the breeding season, Canvasbacks switch to eating both plant and animal matter, including aquatic insects and larvae, mollusks, and small fish.

Canvasback Conservation

Although Canvasbacks are no longer subject to commercial hunting pressure, they continue to face threats on their breeding grounds (wetland drainage and filling) and wintering areas (water pollution, sea level rise, and loss of aquatic plants). Canvasbacks and other waterfowl such as the American Black Duck and the Trumpeter Swan are also vulnerable to lead poisoning from spent shot, as well as fatal exposure to oil spills and uncovered oil pits that they may mistake for ponds.

ABC supports clean coastal habitats and improvements of water quality for wintering Canvasbacks and other waterfowl. We opposed the Environmental Protection Agency's loosening of regulations on the designation of Waters of the United States, changes that allow drainage and filling of many small wetlands important to ducks. ABC also advocates for the North American Wetland Conservation Act, which just received a funding increase.